Updates:

- 2018-03-02: Making link to separate article on installing firmware easier to notice.

- 2018-07-28: Travis Poppe has a 3-D printed case for this you can download and print: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2923619

- 2020-05-01: Reformatting for current WordPress. Renaming some images.

This is a fairly detailed guide to configuring a cheap ESP8266 WiFI module to act as a WiFi modem, then wiring it up to any computer with a traditional RS-232 port.

It can be as simple as hooking up four wires, or many more wires, or even making a breadboard prototype:

ESP8266 to “3-wire” RS-232 TTL adapter.

Wiring up a “full” RS-232 to TTL adapter.

ESP8266 to RS-232 on a breadboard.

Hardware Needed

- ESP82660-12E NodeMCU 1.0 development module (or a NodeMCU ESP-32S module)

- microUSB cable and power source (either powered by a computer’s USB port, or a standalone USB power supply like a phone charger)

- RS-232 to TTL adapter that operates at 3.3V.

- Female-to-female jumper wires (or male-to-male jumper wires and a breadboard)

- RS-232 cable (and possibly an RS-232 gender changer or NULL modem adapter)

Software Needed

Currently, we have to download and build the special Zimodem firmware, but as soon as I figure out what it takes just to load a pre-built binary, this section will be removed.

- Serial Drivers for the development module you choose.

- Zimodem firmware for the ESP by Bo Zimmerman.

- ESP firmware flash tool (or Arduino IDE if you want to download and build the source code yourself).

HARDWARE

ESP Development Module

The ESP8266 is a tiny WiFi device that can also run custom code. The development module version has a built-in USB-Serial adapter that can be used for debugging and loading firmware, and also gives a convenient way to power the module.

- I started out with a NodeMCU ESP8266-12E module from Amazon for $8.29, available with 2-day Prime shipping. I later ordered a batch of five for $25 from this e-Bay reseller (shipped from the US). You can also find them for under $4 each if shipped from China.

- The ESP32 is also supported, like this ESP32-WROOM-32 NodeMCU 32-S module for $12.99 on Amazon. They can be also be found for under $6 shipped from China. The ESP32 adds support for Bluetooth, but the firmware we will be using currently does not make use of it. The only real reason to use it is that Zimodem for ESP32 will be built using standard RS-232 signals, while the Zimodem build for ESP8266 has inverted RS-232 signals for Commodore computers, and will require some additional setup to make work on non-Commodore machines.

- Even an under-$2 ESP-01 will work if you are not needing full RS-232 signals like hardware flow control and carrier detect. However, you will need more hardware to program it and power it, so I just stick with one of the development boards that has USB built in. (It actually cost me more to order an ESP-1 plus the USB programming adapter than to buy one of the devkits with everything built in.)

microUSB Cable and power supply

You will need a standard USB to microUSB cable to hook the ESP to a computer so you can load the firmware. Most Android phones use this type of cable, as do things like the Raspberry Pi. If you don’t have one, you can probably buy one at the local gas station.

This cable will also provide power for the ESP module, so it will need to be hooked to a computer’s USB port, or into a USB power supply like a phone charger. Again, commonly available even at the local gas station.

RS-232 to TTL Adapter

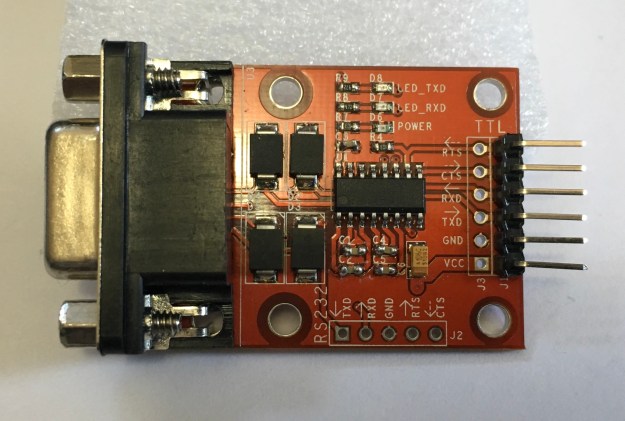

The ones I found have a standard DB9 female connector and contain circuitry that will convert the 3.3V chip-level TTL signals used by the ESP chip to standard 12V RS-232 levels that a computer uses. These will often will come with a short 4-wire jumper cable that can be used to hook them up to the ESP module.

- If all you want is just transmit and receive (referred to as a “3-wire” hookup), you can go with a simple one like this $7 one from Amazon (there are also ones under $6), or find them for less with slower shipping (under $1 shipped from China). These provide hookups for TX (transmit), RX (receive), VCC (power) and GND (ground). For simple uses, this may be all you need. MAKE SURE THE ADAPTER SUPPORTS 3.3V! Some only work with 5V and are not compatible with the ESP modules. WARNING: Some of the ones I tried that claimed they operated at 3.3V did not, so it may take some trial and error.

- If you also need hardware flow control (referred to as a “5-wire” hookup), there are adapters that a add extra connections for CTS and RTS. They are usually cost just a dollar or so more. (Here is a $10 one from Amazon, but I’ve found them for under $4 on eBay.)

- If you need full RS-232 signals, including carrier detect, I have found two sources of adapters that provide TX (transmit), RX (receive), DCD (data carrier detect), CTS (clear to send), RTS (request to send), DTR (data terminal ready), DSR (data set ready), and RI (ring indicator).

- Pololu 23201a Serial Adapter – available asssembled for $11.50, or in a partial kit for $9.95. This adapter uses one row of 10 pins, and is breadboard friendly. However, I have had been some issues with this part, so I cannot currently recommend it. If you try it and can get it to work, please let me know.

- AIBANS.BREAKOUT Adapter – available through Amazon for $4.68+$3.03 shipping from California reseller MD Fly, or $3.25+$3.65 standard shipping through their e-Bay listing. (On eBay, you can get a shipping discount for ordering multiple units.) This one works great for me, but it uses a dual-row of pins so it is not breadboard friendly.

“3-wire” RS-232 to TTL adapters, providing just TX and RX.

“5-wire” RS-232 to TTL adapter, adding CTS and RTS for flow control.

Full RS-232 to TTL adapters, providing all signals (TX, RX, CTS, RTS, DTR, DSR, DCD, RI).

Jumper Wires (Female-to-Female)

Most of the RS-232 to TTL adapters I have seen come with a set of jumper wires with female ends. They slide over the pins on the board, and then slide over the pins of whatever you are connecting it to. They allow hooking up parts without needing soldering skills or even a breadboard. I find bundles of 40 of these for under $3.

Optional: Breadboard and Male-to-Male Jumper Wires

Optionally, if you want something that is a bit more “stable” (without exposed pins and such), you can use a breadboard and male-to-male jumper wires, then plug everything up and jumper them together.

RS-232 Cable and Adapters

You will need a cable to go from your computer’s RS-232 port to the adapter. Your cable will depend on the type of RS-232 to TTL adapter you have. All the ones I have use DB-9 female connectors, but there are some that use a male connector.

For example, my Radio Shack Color Computer has a 4-pin DIN connector for the built-in Serial I/O port. Back then, cables where made that had a male 4-pin DIN connector on one end (to plug into the CoCo) and a male DB-25 connector on the other (to plug into a modem). If I could find my old cables, I could use them, but I would still need a DB-25 to DB-9 adapter to go between that cable and the smaller DB-9 connector of the RS-232 to TTL adapter.

Another common type of serial cable is a NULL modem cable, which was used to hook two computers together by serial ports. I have a NULL modem cable that has the male 4-PIN DIN connector on one end and a female DB-9 on the other. Since it is a NULL modem cable, it has the TX and RX lines swapped so it can plug directly to a “modern” PC’s serial port DB-9 male connector. To use this cable, I needed a male DB-9 to male DB-9 NULL modem adapter, which will swap the TX and RX again, making it a normal cable like the RS-232 to TTL adapter requires, and change the gender so it will plug into the TTL adapter.

I also have the Deluxe RS-232 Program Pak, which provides a full RS-232 port with a female DB-25 connector. To use that, I ordered a standard male DB-25 to male DB-9 cable from Amazon. This will plug directly from my RS-232 Pak to the RS-232 to TTL adapter.

Basically, you will need whatever serial cable your system requires and a way to convert it to plug into a DB-9 connector.

SOFTWARE

The ESP modules have their own software installed, and it includes a command mode where you can use “AT” commands (similar to the old Hayes Smartmodem standard) to do various WiFi things. But, this is not setup to emulate an old modem connection. Instead, we will use Bo Zimmerman’s excellent replacement firmware called Zimodem. He provides the source code, but you will have to download and build it, then load it into your module.

I am now maintaining a special version of Zimodem that has things set up for normal RS-232 use. (By default, the original Zimodem works in a Commodore mode for 8266, and normal for ESP32. My version works in normal mode for both.)

Serial Drivers

Most of the low-cost ESP parts use serial hardware that is not recognized by a Mac or PC (not sure about Linux). If you plug up your ESP part to your computer and it is not recognized as a serial port (Like COM5: on windows, or /dev/cu.SLAB_USBtoUART on Mac), you will need drivers.

Most sellers will provide links to where to find drivers. For the Amazon parts I purchased, they used the CP2012 chipset, and I had to download and install the drivers for it. Once installed, you can plug the ESP module up and it should show up as a new serial port device.

Firmware Flash Utilities

Because of the various methods available to install ESP firmware, I have split them out into a separate article.

Please read this article for details on how to load the firmware onto the module without needing to install the Arduino IDE, download the sources, and build it yourself.

Testing Zimodem

Once the firmware has been installed on the module, you can open up the Serial Monitor in the Arduino IDE and verify it is running. You will need to set it to 1200 baud to match the default speed used by Zimodem, and have it set to “Carriage return“. You can type “AT” and it should respond with “OK”. You can type “AT+CONFIG” and it should startup the configuration process.

If you get this far, you are ready to hook it up to the RS-232 to TTL adapter and then connect it to your computer.

WIRING

Simple 3-wire hookup

For simple serial ports, all you may need to do is hook up TX (transmit), RX (receive), VCC (3.3v) and GND (ground) between the ESP module and the TTL adapter. Here is the pinout of the NodeMCU ESP8266-12E module:

All you have to do is connect the jumper wires between the pins of this module, and the matching pins on the TTL adapter. Some TTL adapters may have TX and RX reversed, but in general you want to hook up like this:

3-wire hookup:

TTL ESP8266

=== ==================

2 RX <------ TX GPIO1 (TX)

3 TX ------> RX GPIO3 (RX)

5 GND <------ GND GND

VCC <------ 3V3 3.3V

For one of my adapters, I found it would not work using the 3.3V pin, and I had to switch to using the Vin (voltage input) pin, which would be the 5V coming off the USB connection. *THIS IS NOT RIGHT since the I/O pins of the ESP modules are mean to handle 3.3V and not 5V, so use caution. If you absolutely can’t get it to work on 3.3V, you can do what I did, but you risk frying the ESP.* I have other adapters that work properly at 3.3V.

It looks like this (note I am using the incorrect Vin instead of VCC):

WARNING! Keep all the bare metal pins from touching anything else! They could cause a short if they made contact with any metal. To reduce the chance of this happening, I used some of the non-conductive packing foam that the ESP module came in, and plugged the exposed pins into it:

There are still a few exposed pins, and on the top side of the module are lots of metal parts and solder connections, so just make sure you keep away from any metal parts!

Now I was able to hook this up to my Color Computer’s Serial I/O port and load up an old terminal program and start using Zimodem.

RS-232 Challenges – Carrier Detect and Flow Control

A quick tidbit on RS-232…

There are nine lines used for RS-232. They go between the computer (DTE, data terminal equipment) to the device (DCE, data communication equipment). Prepare for many acronyms!

TX and RX: You can think of most lines as one-way paths, with some lines going from the computer to the device, and others going from the device to the computer. For instance, transmit (TX) from the computer goes one way to receive (RX) of the device. On the device, it’s transmit goes one way to the receive of the computer.

CTS and RTS: Some lines are used for flow control. Each device has a request to send (RTS) output line that goes to the other side’s clear to send (CTS) input line. CTS goes to RTS, and RTS goes to CTS, similar to have TX and RX and handled. For example, the computer turns on RTS (request to send) to tell the remote device it is okay to send data. The remote device reads this on it’s CTS (clear to send) pin. The reverse is also true, with the remote device’s RTS going to the computer’s CTS. Thus, if using flow control, the computer or device only send when their CTS (clear to send) line is active.

DCD: The device may also use carrier detect (DCD). For a telephone modem, when a call is connected, the device will turn on carrier detect. The computer can read the status of the DCD line to know if a connection is in progress.

RI: There is a ring indicator (RI) that was used by modems to indicate an incoming call. I’ve never used this at all, since the RS-232 interface I had back then wasn’t even wired for it.

DTR and DSR: I am less clear on how all these could be used, but in general, DTR was set by the computer to tell the remote device if it should hangup or not. The computer would “drop DTR” and that would force the modem to hangup. DSR is set by the device to indicate it is there and ready.

Here is a quick chart to explain them, specifically as how they are used by Zimodem:

DTE (Comp.) DCE (Modem) DB-9 Male DB-9 Female ============= ============= pin in out in out pin 1 DCD <--------------- DCD 1 2 RX <--------------- TX 2 3 TX ---> RX 3 4 DTR ---> DTR 4 5 GND GND 5 6 DSR <--------------- DSR 6 7 RTS ---> CTS 7 8 CTS <--------------- RTS 8 9 RI <--------------- RI 9

Some RS-232 interfaces require more than just TX and RX to be happy. The Color Computer’s RS-232 Pak, for example, uses a 6551 UART chip. This chip will not receive data unless it sees carrier detect (DCD). Old telephone modems would provide this DCD signal when a call was in progress, and drop the signal when the call ended This gave the computer a way to know if a connection was established or not. Unfortunately, this signal is not present in a 3-wire connection.

Faking carrier detect and flow control

It was possible to hook two computers together without a modem by using a NULL modem cable. These cables would swap TX and RX, so one computer’s transmit would end up at the other computer’s receive. They would also often do some trickery to force the DCD signal to be active. They did this by tying some of the pins on the RS-232 port together:

If we really don’t care about this missing lines (like CTS/RTS flow control, DTR/DSR, etc.), we can modify the RS-232 to TTL adapter so make it provide a fake DCD signal back to the computer.

Using the above diagram as a reference, I was able to solder a few pins together and use a short piece of wire to recreate it on real hardware:

This modification makes it so anytime the computer enables DTR, it will make DCD and DSR read as if they are enabled. It is creating a fake status by looping the DTR signal back into the DCD and DSR input pins.

Since this 3-wire hookup also does not have CTS and RTS, if the computer is expecting CTS (clear to send) to be active, that can never happen and thus it can never send. This modification ties the outgoing RTS (request to send) back to the incoming CTS (clear to send). When the computer enables request to send, to tell the remote device it is okay to send, it will read that same signal as if the remote device sent in it’s own request to send (coming in on the CTS line of the computer).

So much stuff.

Suffice it to say, but tying these lines together, it will fool the RS-232 device into thinking there is an active carrier detect and data terminal ready signal from the demote device anytime DTR is enabled. And, it will see a clear to send signal anytime it turns on read to send… Loopy goodness!

With that said, if you don’t want to solder, you could pick up these RS-232 jumper devices and create the connection this way. Note that in this example, I do not have CTS and RTS tied together. For my specific test, I did not need it, but other RS-232 interfaces may require it.

5-wire hookup – Implementing real CTS/RTS flow control

Another option is to use an RS-232 to TTL adapter that actually provides more of these signals. For a bit more, you can find an adapter that has CTS and RTS as well:

By adding two more wires between Zimodem and the adapter, you can use real hardware flow control. Zimodem will only send when it sees a clear to send signal from the computer, and if Zimodem can’t handle all the data it is receiving, it will disable it’s request to send, so the computer’s CTS line indicates “stop sending me stuff!”

TTL ESP8266

=== ==================

2 RX <------ TX GPIO1 (TX)

3 TX ------> RX GPIO3 (RX)

5 GND <------ GND GND

7 RTS ------> D1 GPIO5 (CTS)

8 CTS <------ D2 GPIO4 (RTS)

VCC <------ 3V3 3.3V

This configuration still would not work for my 6551-based RS-232 Pak. I would still need to fake the carrier detect.

Full-wire hookup – as real as it gets

The final, and best, solution is to use an RS-232 to TTL adapter that actually provides all the signals that Zimodem supports and that your RS-232 interface may require. This requires hooking up even more wires (ten total):

TTL ESP8266

=== ==================

1 DCD <------ D4 GPIO2 (DCD)

2 RX <------ TX GPIO1 (TX)

3 TX ------> RX GPIO3 (RX)

4 DTR ------> D6 GPIO12 (DTR)

5 GND <------ GND GND

6 DSR <------ D7 GPIO13 (DSR)

7 RTS ------> D1 GPIO5 (CTS)

8 CTS <------ D2 GPIO4 (RTS)

9 RI <------ D5 GPIO14 (RI)

VCC <------ 3V3 3.3V

Mine looks like this:

If all those wires get to you, you can also do the same thing on a breadboard:

Configuring Zimodem: Commodore versus The World

Although the wiring seems complete, there is one final issue that needs to be solved.

Zimodem, when built for the ESP8266, inverts all the RS-232 signals. This is because that is how Commodore computers did it, and Zimodem was designed for Commodore users. Commodore inverts HIGH and LOW from the standard, so all signals have to be inverted in

Zimodem from their defaults. On Commodore, “HIGH” means active. For RS-232, “LOW” means

active.

What this means is even if you have the carrier detect wired up properly, Zimodem is going to send the opposite signal. When a connection is in progress, the signal will read as “no carrier” to a normal RS-232 interface. When Zimodem is ready to receive data, the request to send will look like the opposite.

This causes huge issues :)

If you are using my special build of Zimodem, you can skip this section. I already pre-configure my version as follows.

Fortunately, Zimodem is fully configurable. Using simple “AT” commands, you can change the behavior of any of the incoming or outgoing RS-232 signals that Zimodem uses. All you have to do is be able to send some commands and then save the Zimodem configuration. Here is the summary:

AT S Settings: ============== 0=HIGH is active (defualt). 1=LOW is active. 2=force HIGH 3=force LOW Sig SReg Default RS-232 Standard === === ======= ================= DCD S46 0 1 (force LOW) CTS S48 0 1 (force LOW) RTS S50 0 1 (LOW is active) RI S52 0 1 (LOW is active) DTR S54 0 1 (LOW is active) DSR S56 0 1 (LOW is active)

You can set these commands one at a time, like:

ATS46=1 OK ATS48=1 OK ...etc...

…but you may find that the moment you toggle one of them, you appear to be locked out. This is because the inverted defaults actually work to our advantage. On my interface, I need DCD before I can receive. Zimodem has no carrier, so it is sending out the inverted “there is no carrier” signal, which reads as “carrier detect” for me. The moment I “fix” that so it sends the normal signal, I suddenly have no carrier and can no longer receive data.

You may choose to send all the commands in one line:

ATS46=1S48=1S50=1S52=1S54=1S56=1

However, as soon as that is done, you may not see “OK”. Carrier detect is still flipped… You may be able to still send commands, but you would be typing blind if your interface requires DCD before it will receive. Because of this, I like to force DCD to be always on:

ATS46=3S48=1S50=1S52=1S54=1S56=1

That command flips everything, but makes sure DCD (S46) is forced low (3), so it appears like a carrier is always present. This lets me communicate with Zimodem at all times.

If I were running a BBS that relied on detecting carrier, I would have to leave that at S46=1 and just send commands blindly. (BUT, one of my old terminal programs, Greg-E-Term, is not coded in a way that makes this work. It seems if there is no DCD, it doesn’t let me send anything at all. Other terminal programs I have do not behave this way, so I consider it an issue with what GETerm was designed to do.)

Confusion Conclusion

With all of this said, there are probably still many omissions. A future article needs to be a summary of useful Zimodem commands and tutorials on how to use it.

I also want to cover another alternate approach to having to configure with all those ATS commands. In my case, I simple modified the source code so the version I built had them setup the normal way so I never had to do any configuration.

And I need to document how to just install a binary without using Arduino IDE.

Until then… Comments greatly appreciated.