See also: part 1, part 2 and part 3.

In the first part of this series, I didn’t explain who Alex Evans is or what his BASIC UTILS are. And I may not in this part, either. Rest assured, Alex Evans fans, I will be getting to this soon eventually.

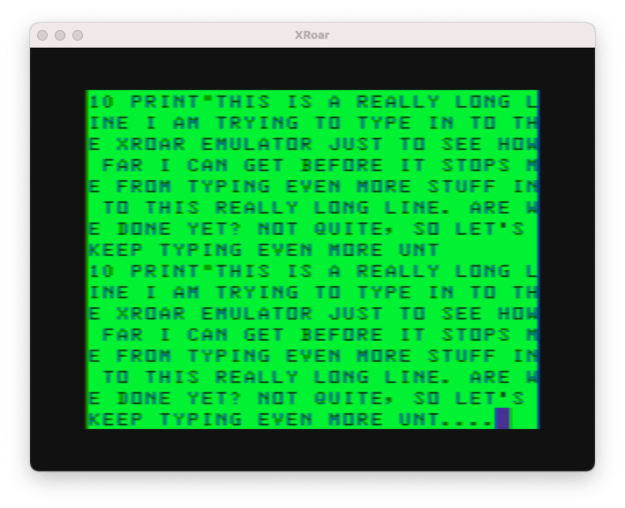

The focus right now is looking at ways to make BASIC program lines that are longer than the 249 characters we can type in to the 251-byte input buffer. One way to do that is manually.

Previously I showed a three-line BASIC program that did three PRINT commands. By PEEKing through the memory of that program, we could see how it was stored:

Now that I understand how those bytes are stored, it seems it would be easy to copy them somewhere else in memory, and adjust the BASIC pointers for “start of program” and “start of variables” to reference the new location and see if it works.

And it almost does… Here’s a program that does it:

0 ' BASCLONE.BAS

10 ' START OF PROGRAM

20 ST=PEEK(25)*256+PEEK(26)

30 ' START OF VARIABLES

40 EN=PEEK(27)*256+PEEK(28)

50 ' SIZE OF PROGRAM

60 SZ=EN-ST

70 PRINT "THIS PROGRAM IS AT:"

80 PRINT "START: &H";HEX$(ST),"END: &H";HEX$(EN)

85 'PRINT "ARYTAB: &H";HEX$(PEEK(29)*256+PEEK(30)),;

86 'PRINT "ARYEND: &H";HEX$(PEEK(31)*256+PEEK(32))

90 ' NEW START

100 NS=ST+&H1000

110 PRINT "COPYING TO &H";HEX$(NS)

120 ' CLONE TO HIGHER MEMORY

130 FOR I=0 TO SZ

140 POKE NS+I,PEEK(ST+I)

150 NEXT

160 ' SHOW NEW LOCATION

170 PRINT "PROGRAM COPIED TO:"

180 PRINT "START: &H";HEX$(NS),"END: &H";HEX$(NS+SZ)

190 END

200 PRINT "START: &H";HEX$(PEEK(25)*256+PEEK(26)),"END: &H";HEX$(PEEK(27)*256+PEEK(28))This program will start by showing the start and end of the BASIC program, and then it will copy that memory to 4K higher in memory (current start plus &H1000). After that, it prints the new start/end locations and ENDs. After running, we’d manually do the POKEs to set locations 25/26 and 27/28 to those values, and then we could RUN 200 to see if it works.

I am using HEX so it’s easy to figure out the MSB (most significant byte) and LSB (least significant byte) of the addresses for the later POKEs. You can see that I POKE 25 and 26 to the first two and last two digits of the new “START” address, and the same with 27 and 28 and the new “END” address.

Then I RUN 200 and it prints where it thinks the program is. It works!

Sorta. If I attempt to EDIT this program or add a new line, I end up with a corrupt program. There’s clearly more that needs to be done for this to really work, but it’s a good proof-of-concept.

Rather than figure out what all I need to do to make this work, I tried using the PCLEAR command. I know it will relocate the current BASIC program and adjust variables as needed. By repeating the same steps as before, I can see the “new” program is higher in memory, then by doing a PCLEAR 4 (which is what it was already set to), it relocates the BASIC back to where it should have been. I can then add a line 81 END and RUN it to see it print the location — matching the original.

Okay, that’s cool. Probably not the correct way for it to be cool, but it does appear to work. For me. Sorta.

Creating BASIC where there was none

The real goal here is to create a BASIC program that has a line that goes well beyond the 249 character tapeable line length.

Going back to my earlier example that had PRINT”A”, we can see that the PRINT token was a value of 135 (&H87), and a quote is 34, then the character(s) to print, followed by another quote 34, then the zero at the end of the line. As a simple test, I will try to create a program that PRINTs the hex digits from 0 (&H0) to 255 (&HFF). I’ll add a semicolon at the end of each PRINT so each PRINT is on the same line. The program would look like this:

PRINT"0";:PRINT"1";: ... :PRINT"A";:PRINT"B";: ... PRINT"FF";

As a reminder a BASIC program has the format of…

- 2 bytes – Address of next line

- 2 bytes – Line number

- n bytes – Tokenized line

- 1 byte – 0 end of line marker.

To have BASIC create these bytes, I’ll first have it ask for the location in memory to begin creating the BASIC line(s).

Then I’ll use a variable that tracks the address each line starts and remember that so it can be filled in later when the address of the next line is known. I’ll then POKE out the two bytes representing the line number, and then POKE out the bytes for the tokenized line which will be the PRINT token, quote, the ASCII characters for the HEX$() of the number, another quote, then a semicolon and colon. This will repeat for all 255 hex values. Then the 0 will be stored, and after that, whatever address that is will be the start of the next line. That address will be stored back at the first two bytes of the line entry, then the program will end with two zeros marking the end of the program (no address for the next line).

I came up with this program:

0 'IMPOSSIBLE>BAS

10 CLEAR 300

20 PRINT "START: &H";HEX$(PEEK(25)*256+PEEK(26)),"END: &H";HEX$(PEEK(27)*256+PEEK(28))

30 INPUT "START ADDRESS";ST

40 ' CREATE THE IMPOSSIBLE LINE

50 ' LINE START ADDRESS

60 LS=ST

70 ' STORE LINE NUMBER (10)

80 POKE LS+2,0:POKE LS+3,10

90 ' ADDRESS TO STORE DATA

100 AD=LS+4

110 ' STORE REPEATING TOKENS:

120 ' PRINT"x";:

130 ' WHEN "x" IS A HEX NUMBER

140 FOR I=0 TO 255

150 ' BUILD DATA STRING

160 TK$=CHR$(&H87)+CHR$(34)+HEX$(I)+CHR$(34)+";:"

170 'PRINT TK$

180 FOR J=1 TO LEN(TK$)

190 POKE AD,ASC(MID$(TK$,J,1)):AD=AD+1

200 NEXT

210 NEXT

220 ' STORE FINAL TWO BYTES

230 POKE AD,0:POKE AD+1,0

240 ' STORE NEXT LINE ADDRESS

250 MS=INT(AD/256):LS=AD-(MS*256)

260 POKE LS,MS:POKE LS+1,LS

270 ' SHOW RESULTS

280 PRINT "START: &H";HEX$(ST),"END: &H";HEX$(AD+2)Similar to the previous example, I RUN this program, then wait as it generates 256 PRINT statements on one huge line 10, and then do the POKEs for 25/26 and 27/28 shown on the screen, then a PCLEAR 4 to move this new program back to where it should be:

Once that is done, I can RUN to see it fill the screen with hex digits “0” to “FF” (more than fits on a screen), and attempting to LIST the program shows only one line, but only shows the first 249 or so bytes of it:

Checking the size of the program by doing:

PRINT (PEEK(27)*256+PEEK(28))-(PEEK(25)*256+PEEK(26))

…shows that this ONE LINE program is 1782 bytes! That’s quite the long program considering it’s only one line!

Due to the limit of the 251 byte input buffer, we cannot EDIT this line without losing everything after the 249 bytes we can type. If you EDIT and press ENTER, then LIST, you’ll see the program has been truncated.

But, it proves BASIC does indeed not care about how long a line can be.

Prove it!

By typing CSAVE”IMPOSS”,A (for tape) or SAVE”IMPOSS”,A (for disk), you can save the program out in ASCII (text). You could then transfer that file (using the toolshed decb utility or other similar program) to a PC/Mac and look at it in a text editor. This is what I see:

10 PRINT"0";:PRINT"1";:PRINT"2";:PRINT"3";:PRINT"4";:PRINT"5";:PRINT"6";:PRINT"7";:PRINT"8";:PRINT"9";:PRINT"A";:PRINT"B";:PRINT"C";:PRINT"D";:PRINT"E";:PRINT"F";:PRINT"10";:PRINT"11";:PRINT"12";:PRINT"13";:PRINT"14";:PRINT"15";:PRINT"16";:PRINT"17";:PRINT"18";:PRINT"19";:PRINT"1A";:PRINT"1B";:PRINT"1C";:PRINT"1D";:PRINT"1E";:PRINT"1F";:PRINT"20";:PRINT"21";:PRINT"22";:PRINT"23";:PRINT"24";:PRINT"25";:PRINT"26";:PRINT"27";:PRINT"28";:PRINT"29";:PRINT"2A";:PRINT"2B";:PRINT"2C";:PRINT"2D";:PRINT"2E";:PRINT"2F";:PRINT"30";:PRINT"31";:PRINT"32";:PRINT"33";:PRINT"34";:PRINT"35";:PRINT"36";:PRINT"37";:PRINT"38";:PRINT"39";:PRINT"3A";:PRINT"3B";:PRINT"3C";:PRINT"3D";:PRINT"3E";:PRINT"3F";:PRINT"40";:PRINT"41";:PRINT"42";:PRINT"43";:PRINT"44";:PRINT"45";:PRINT"46";:PRINT"47";:PRINT"48";:PRINT"49";:PRINT"4A";:PRINT"4B";:PRINT"4C";:PRINT"4D";:PRINT"4E";:PRINT"4F";:PRINT"50";:PRINT"51";:PRINT"52";:PRINT"53";:PRINT"54";:PRINT"55";:PRINT"56";:PRINT"57";:PRINT"58";:PRINT"59";:PRINT"5A";:PRINT"5B";:PRINT"5C";:PRINT"5D";:PRINT"5E";:PRINT"5F";:PRINT"60";:PRINT"61";:PRINT"62";:PRINT"63";:PRINT"64";:PRINT"65";:PRINT"66";:PRINT"67";:PRINT"68";:PRINT"69";:PRINT"6A";:PRINT"6B";:PRINT"6C";:PRINT"6D";:PRINT"6E";:PRINT"6F";:PRINT"70";:PRINT"71";:PRINT"72";:PRINT"73";:PRINT"74";:PRINT"75";:PRINT"76";:PRINT"77";:PRINT"78";:PRINT"79";:PRINT"7A";:PRINT"7B";:PRINT"7C";:PRINT"7D";:PRINT"7E";:PRINT"7F";:PRINT"80";:PRINT"81";:PRINT"82";:PRINT"83";:PRINT"84";:PRINT"85";:PRINT"86";:PRINT"87";:PRINT"88";:PRINT"89";:PRINT"8A";:PRINT"8B";:PRINT"8C";:PRINT"8D";:PRINT"8E";:PRINT"8F";:PRINT"90";:PRINT"91";:PRINT"92";:PRINT"93";:PRINT"94";:PRINT"95";:PRINT"96";:PRINT"97";:PRINT"98";:PRINT"99";:PRINT"9A";:PRINT"9B";:PRINT"9C";:PRINT"9D";:PRINT"9E";:PRINT"9F";:PRINT"A0";:PRINT"A1";:PRINT"A2";:PRINT"A3";:PRINT"A4";:PRINT"A5";:PRINT"A6";:PRINT"A7";:PRINT"A8";:PRINT"A9";:PRINT"AA";:PRINT"AB";:PRINT"AC";:PRINT"AD";:PRINT"AE";:PRINT"AF";:PRINT"B0";:PRINT"B1";:PRINT"B2";:PRINT"B3";:PRINT"B4";:PRINT"B5";:PRINT"B6";:PRINT"B7";:PRINT"B8";:PRINT"B9";:PRINT"BA";:PRINT"BB";:PRINT"BC";:PRINT"BD";:PRINT"BE";:PRINT"BF";:PRINT"C0";:PRINT"C1";:PRINT"C2";:PRINT"C3";:PRINT"C4";:PRINT"C5";:PRINT"C6";:PRINT"C7";:PRINT"C8";:PRINT"C9";:PRINT"CA";:PRINT"CB";:PRINT"CC";:PRINT"CD";:PRINT"CE";:PRINT"CF";:PRINT"D0";:PRINT"D1";:PRINT"D2";:PRINT"D3";:PRINT"D4";:PRINT"D5";:PRINT"D6";:PRINT"D7";:PRINT"D8";:PRINT"D9";:PRINT"DA";:PRINT"DB";:PRINT"DC";:PRINT"DD";:PRINT"DE";:PRINT"DF";:PRINT"E0";:PRINT"E1";:PRINT"E2";:PRINT"E3";:PRINT"E4";:PRINT"E5";:PRINT"E6";:PRINT"E7";:PRINT"E8";:PRINT"E9";:PRINT"EA";:PRINT"EB";:PRINT"EC";:PRINT"ED";:PRINT"EE";:PRINT"EF";:PRINT"F0";:PRINT"F1";:PRINT"F2";:PRINT"F3";:PRINT"F4";:PRINT"F5";:PRINT"F6";:PRINT"F7";:PRINT"F8";:PRINT"F9";:PRINT"FA";:PRINT"FB";:PRINT"FC";:PRINT"FD";:PRINT"FE";:PRINT"FF";:Pretty cool! A one line program that is 1700+ bytes long. Sweet!

There’s got to be an easier way…

And we’ll do that in the next part.

Until then…